Most of us have lost money in startups: the asset class is inherently risky, markets are often illiquid, and entrepreneurs are not always straightforward or forthcoming. The owners and founders may manage cash poorly, be grossly negligent in their duties, and employ some tricks to paint themselves in a better light. We as investors can blame the companies and management, but we should also take responsibility for being naive or negligent ourselves in some instances. In this post, I want to explain some ways to avoid the issue altogether, so we don’t lose money and if we do, we can at least learn from the mistake.

I’ve been investing in startups on Seedrs and Crowdcube since 2013 and also have raised three funding rounds for my startup on Seedrs since 2016. I review most campaigns on a weekly basis to understand best practices to help improve our own campaigns and also to identify any patterns of tricking the investors, some of which I’ve outlined below.

The Lack of Information

One of the biggest issues investors face is lack of information, particularly when it comes to management, business, and financial changes that may be reflected in news and company filings for private companies. Traditional media coverage may be thin or nonexistent, and start-ups may use this to their advantage by not drawing attention to the changes.

On equity crowdfunding platforms, while the platform performs due diligence for factualness of statements and claims, individual risk profiles are not accounted for, and individual investors should look more closely at the overall situation. Due to my own frustrations with similar issues in the public markets, I started building the original CityFALCON product, and now, 5 years later, we can help other P2P and angel investors too.

Another rich source of information is company filings. These are easy enough to find for public companies, but private companies are much harder to come by. In the UK, some may publish on the LSE’s Regulatory News Service (RNS), but all must publish with Companies House and the Gazette. In the United States, only public companies have to file with the SEC, but even private companies have to file with their state’s company registry – of course, there are 50 US states, so sometimes it may take a while to find and navigate all of these agencies. New York, Delaware, and California will probably account for many investment targets, but there are plenty of other targets in other states, too.

A third source of pre-investment due diligence information comes in the form of analytics, like sentiment analysis, and information sourced from alternative data, like customer ratings. Even if a company has little news coverage, a sentiment analysis of Tweets may uncover an interesting trend, or customer ratings may indicate the product is unacceptable to the public, meaning one may want to avoid the investment for now.

Information helps people avoid some of the pitfalls of P2P investing on equity crowdfunding platforms, but there are still some tricks to watch out for. Much of it actually relies on asymmetries of information, so having as much as you can tends to make these tricks apparent.

Faking FOMO

I’ve been very candid about FOMO (fear of missing out) being one of the key reasons why investors invest in most asset classes. The cryptocurrency craze of winter 2017-2018 is one of the most spectacular and illustrative examples, and the race to web-ify everything during the dotcom boom at the turn of the millennium is another good example. The same FOMO concept is often applied by entrepreneurs looking to raise funds.

FOMO is a socio-emotional play, and, unfortunately, some companies create fake FOMO. For instance, once their crowdfunding campaign is live, they might claim that they raised £1m in a few minutes/hours. If everyone else is flooding into this investment, then they must have done their due diligence and it must be a good sign, right? Investors feel that the investment is worthy, and social activity amplifies this feeling. But did the company really just post their investment idea and it was so great that £1,000,000 just flooded right in? Probably not. What they don’t tell you is how they chased investors for 3 to 6 months, secured most of the £1 million funding quietly, then ran their round in ‘private mode’ for a few days. Finally, when they “go live”, the public see all this capital pouring into an investment and want a piece of the equity offered.

As an investor, if you do not do your research and just invest based on FOMO, things may not turn out well. The earliest money probably did do some research, but there could be any number of agreements that give preferential treatment to them, for example to VCs, that those rushing to invest do not receive. By investing without due diligence, you can easily fall prey to this tactic and end up with fewer rights and a bad investment.

Increasing Valuation but Not Share Price

This is what amazes me the most about investing in private markets. In the public markets, we focus on the price per share, e.g., you buy Apple stock at $100 and sell for $200, you make money and you’re happy. In private markets, most people focus too much on valuation and completely disregard dilution. For instance, investors are happy when they hear high valuation numbers for companies they have invested in without realising that they may not have made a return anywhere close to the jump in the valuation of the company. The jump in valuation may have occurred mainly because of equity issues, which provided needed capital but also diluted the equity.

For example, the company used to have 100,000 shares, but after a couple equity raises, they have 150,000 shares. If the company valuation doubled, it doesn’t mean the share price double for existing investors. £1 million valuation is 100,000 shares at £10 a share, and £2 million valuation with 150,000 shares is £13.33 per share. That’s a return of 33%, not 100% as one might mistakenly assume from the higher valuation. Dilution can occur even without fund raises, which happens when stock options are exercised and new shares are issued to cover the options.

Back in 2013, I had invested in a well-known and disruptive startup, and their valuation has jumped at least 10 times now from 2013, but my return has been less than 2 times the money. Companies emphasize the valuation jump because it looks good and they can then downplay the poor stock price change. 100% return over 5-6 years is acceptable in public markets, but in private equity and startups, there is generally much more risk, and investors should be compensated for that.

I could but I’m going to avoid putting in a graph of some companies that are highly valued but have not provided a good return on investment. Instead, I’ll share an example of a company that has shown good capital appreciation at each of their rounds on Seedrs. LandBay has provided a 17x return on investment from their first-round in 2014. Has their valuation increased? Of course. But importantly for investors, this also translates to an increase in the share price. This is what their share graph looks like.

Providing a strong investment return to our investors is one of the key things we focus on at CityFALCON. We have decided to stay lean to conserve cash while we build the product. This helps us avoid taking big (VC) money but also ensures our valuation appreciation is also partially fuelled by improved product and market potential than simply raising money while customers wait on a product. This has allowed us to show a strong return on investment as the valuation has risen.

For those who invested in the first round back in 2014, their money has tripled, and the return is much higher if you consider the SEIS and EIS tax benefits. Of course, future results are never guaranteed by past performance – they can only indicate a trend, not a sure investment.

Not Providing Enough Information or Forcing Investors to Gloss Over the Documents

We have seen several campaigns from popular FinTech brands wherein investors have not even had time to consume the content, ask relevant questions, and think about the valuation. The campaign is rushed to a close, in part because the target funding threshold is exceeded early due to money secured pre-campaign (as mentioned above). The FOMO kicks in and investors rush to invest before the round closes without reading the documents and performing proper due diligence. Or sometimes the documents provided are silent on important questions, stonewalling investors who want to dive deeper. Personally, if I can’t read and research about the company that I want to invest in, I’d stay out.

Relying on a Lack of Investor Due Diligence on the Company, Sector, and Competitors

Even with sufficient internal information and absent FOMO and lack of pressure to close the funding round, investors sometimes overlook researching the relevant sector, competitors, and third-party data regarding the company. The trick here can be pressure to Invest Now!, or it could be misdirection to focus on the hype of the problem and solution rather than the financial and business situation surrounding the company. Sometimes the misdirection isn’t even intentional but management’s blindness to the business situation.

Regardless of the reason, investors should not neglect proper due diligence. One of the easiest places to start is company filings and news regarding the company. Analytics and alternative data, like customer ratings, are important. Moreover, the direction and state of the sector is important, and one should look at both the sector in general and individual companies (i.e., the competitors). Of course, CityFALCON can help P2P and angel investors procure this information so they don’t have to look at multiple sources. We even track individual products so you could even create a watchlist of competitor products to track how the industry is developing while your investment target develops their own product or service.

Misdirection on Management Ethics, Conduct, and Background

Companies live or die by their management, so it’s critical to know who is running your investment target. I typically invest a small amount in the first campaign of a company and monitor how they behave. This includes how management updates investors, whether questions are answered promptly, and how forthcoming documentation and answers are. Good management knows how to communicate with investors and provide sufficient information to keep investors informed.

If there is a heavy emphasis on management’s background (where they worked, relations to well-known brands, etc.), but little communication, it is a red flag. For the first round, it is impossible to avoid, as previous work experience is of course important. But once the company has been their focus for a couple years, their experience at previous firms is less important. The main exception is clearly demonstrated ability to leverage relationships at the old firms to generate revenue for their current business.

Encouraging Investors to Blindly Follow VCs and Institutional Investors

There is a tendency for investors to follow venture capitalists and institutional investors because it is assumed that these parties do their proper due diligence and will only invest in good investments. Putting aside the fact that most startups fail and that VCs don’t care if 5 investments go to zero as long as the 6th jumps twenty-fold, VCs and institutions have certain advantages over ordinary investors.

One such advantage is preferential treatment. Just because a venture firm invested in a company does not mean you, as an ordinary investor, will receive the same share class. The VC shares may be convertible to debt, provide for extra voting power, or have reverse vesting terms that favour the VC. The VC is also likely to force management to reveal more confidential information than will be available to the public, including management accounts that even the most transparent firms would not publish publicly.

Another important factor to consider is that VCs don’t care about the company or the other shareholders. If the VC decides to use its voting power to force a decision that dilutes everyone else’s shares but not the VC’s shares, they will do it at your expense. Or perhaps they think the company will fail, and they see saleable assets equals their debt after conversion at a favourable rate to them. They might convert, force a bankruptcy, and take all asset proceeds, leaving ordinary investors with nothing.

A further point to consider is synergy opportunities within the VC’s portfolio. With considerable voting power, VCs may be looking to leverage synergies in their portfolio that may not benefit the other shareholders. This could even be grabbing assets of one company, killing off the company for a profit, and moving the assets to another, more profitable firm in the portfolio. This includes intellectual property, and this is the essence of vulture capitalism.

I do not intend to say that VCs and institutions are always bad to follow or want to inherently harm other shareholders. They’ll do sophisticated due diligence, and they’ll take actions that benefit you just as quickly as actions that will harm you, as long as they stand to make money. Just be aware of what may happen and how to avoid pitfalls.

Misrepresenting ‘Users’

The number of users is a major metric for investors, because it is at least somewhat indicative of market demand and traction. The more users the better. Of course, for new companies, the number of actual users – people using the product or service as often as and to the extent which the company intends for the product or service to be used – can be quite low. How many half-finished products do you use? A few early adopters do not a market make, nor does that small number impress investors.

Thus, companies inflate their user numbers in all kinds of ways. Some use pre-launch registrations as a “user number”, while others use site or product registrations. This could be orders of magnitude larger than the number of people who actually use the product as intended. Have you ever signed up to hear more about a product once it becomes available? For some unscrupulous companies, you may be a “user”, even if you’ve never seen more than a screenshot of a proof of concept.

The only way to defend against this type of trick is to ask for clarification of the term “user”, and perhaps through some extrapolation with third-party mentions (customer reviews, number of news stories, etc.). Company track record with transparency here is essential, too. We believe we set a model example in the transparency category, with a blog post on our own fundraise and valuation with plenty of detail.

Not Disclosing the High Burn Rate and Low Runway

Burn rate and runway are probably the two most important current financial metrics. Financial considerations are not the only important ones, but if you cannot pay employees or suppliers, it is very hard to run a business. Many companies will blow millions of investor cash on acquiring customers, often with Minimum Viable Products that generate buzz but not staying power, then when they’re running low on cash, race to get more funding. This pressures management to employ FOMO-inducing tactics as mentioned above to secure funding as soon as possible.

Unfortunately, if investors feel their money has been spent recklessly, they may not return. Big investor backing in early rounds may vanish in later rounds, causing the company to struggle to meet its funding targets. Then the company runs out of money and fails. So pay close attention to burn rate, runway, fundraising track record, and how previous investors are treated.

If the company refuses to tell you the burn rate or runway, seriously consider not investing. They are either grossly irresponsible for not doing the financial modeling to find it or they want to hide unflattering numbers.

If the business has been around for a little while, they will have filed some things with regulatory agencies. Again, you can use CityFALCON to check filings, any of the news floating out in the ether, and customer reviews or other alternative data points to get a better sense of the situation.

Using New Funding to Pay off Debt, Unpaid Salaries, and Overdue Suppliers

While funding will eventually be used to pay for salaries and invoices, timing is important. If the bills have gone unpaid, then the company has a money management problem. They should have started raising sooner, not putting suppliers and employees on hold while they raised money that may never come. It causes suppliers to get anxious and potentially stop providing service, killing the company’s product or service in turn. Why would a customer want to pay for something that doesn’t even work? If employees find out, mutiny is not out of the question, and development, maintenance, and every other operation may simply cease. Then customers get upset.

As for creditors, they can be quite aggressive in reclaiming their money, especially if a company or management team has a poor record of repayment. The founders and executives do not want to shut down the company, so sometimes they may even use funds to pay off debt or, even worse, simply service debt. That is an unsustainable capital structure and the company is likely to be fundraising again soon.

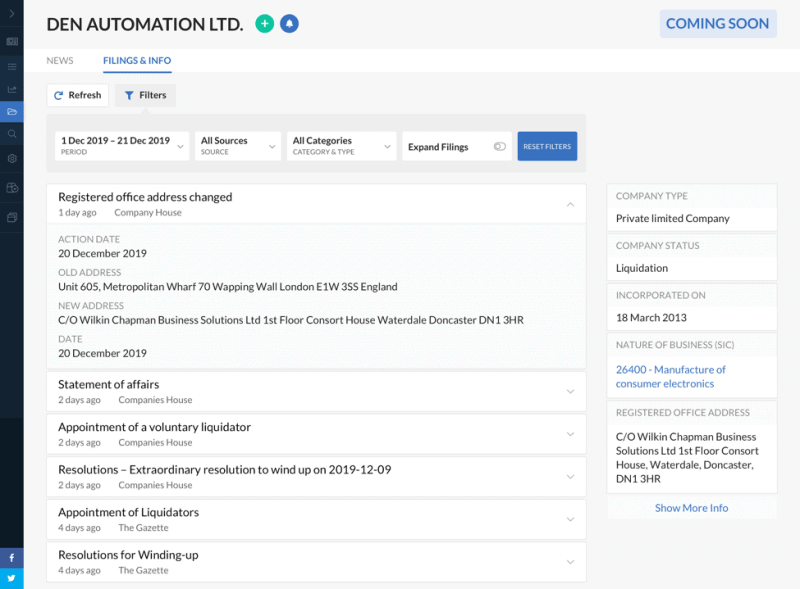

One such example of using equity raises to pay off creditors is Den Automation, which did not work out well for them because they still went into liquidation. They were unable to produce cash flow from customers, but because they had a hardware solution, the product had to be ready before it could be manufactured. But that meant frequent crowdfunded equity raises just to pay suppliers (including for servers designed to work with their product), with investor enthusiasm waning due to low returns and thus less investment. Eventually, the stress was too much and the company went into liquidation.

How CityFALCON Can Help You Avoid These Tricks

The key to responsible and therefore more likely profitable investing, especially in illiquid and private markets, is access to quality information. Delivering the right information at the right time is our goal.

We already provide LSE RNS filings, with Companies House, Gazette, and SEC filings already integrated on the backend but to be launched on the frontend in a couple of months, and US state registries coming soon. Users can see the latest filings and some extracted information, and we plan to extract much more and even calculate various analytics and insights from this data for users, too. This forces fundraising companies to be more honest.

Our tech sifts through 3000+ publications, Twitter, and other sources. Then we deliver this information to the P2P and angel investor automatically. So even if news about a small company doesn’t appear in your usually-watched publications, you can still find it on our platform. That was my goal when I started building my own solution, and now we can offer it to everyone. Alternative data sources, analytics generated for you, personalisation, and more are, as of early 2020, either ready or slated for release in the near future.

Summary

I hope this post helped you recognise some of the most common issues for P2P and angel investors, especially in less regulated platforms like Seedrs and Crowdcube. There are plenty of good opportunities there, but one must be vigilant to avoid negligence, intentional deceit, and poor business practices.

One of our missions is to help individuals with their investing, and for that we’ve partnered with Seedrs to supply them information, which they then deliver to customers on the platform. We also supply plenty of information to our own users, from regular news and research reports to Twitter, alternative data, analytics, and insights. We always have more products and features in the pipeline, too, so we can always help investors minimise information asymmetry. You could try out our platform here.

As of January 2020, we are fundraising on the platform as well. You can learn more on our Invest page and see how a transparent company operates.

Leave a Reply