Introduction

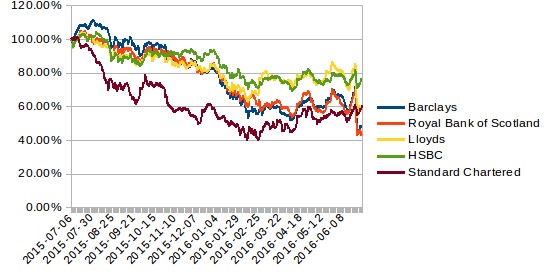

The recent decision made by the UK public to leave the EU brought a wave of uncertainty upon the nation, with investors worried about the potential looming economic implications. With the general consensus prior to the vote that the UK would decide to remain within the EU, the risk of a ’leave’ vote was not priced into markets; and the resulting volatility following the actual ‘leave’ vote was enormous. Investors are now worried that the economic implications of the Brexit could plunge markets across the globe into turmoil. The top 5 FTSE listed banks, by market cap, have already depreciated substantially immediately after referendum results:

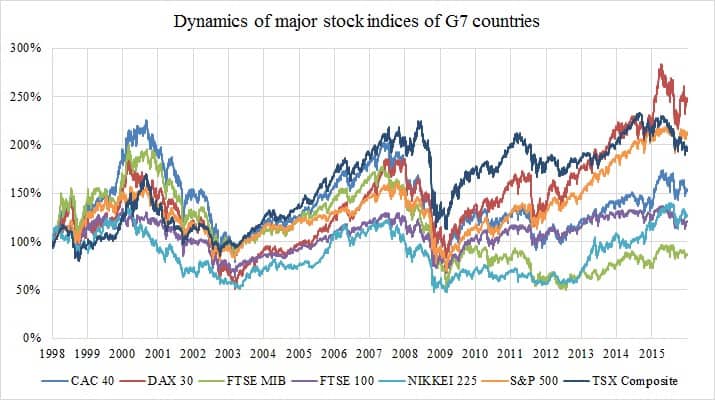

Investors and corporations across the globe now turn their attention to the underlying economic forces that may be affected by the Brexit vote. The health of the underlying economy is generally represented by the dynamics of stock indices of global stock exchanges, as well as commodity prices, interest rates and forex. 2015 was one of the worst years for financial markets, in terms of growth, since the global financial crisis of 2008. The S&P 500 and DJIA actually faced overall yearly declines of 0.7% and 2.3% respectively. Now, as we look forward to 2016 & 2017; historically low interest rates across the globe, paired with a looming debt bubble, and increasingly bearish market sentiment from investors across the globe leads to a negative economic outlook going forwards.

Implications to UK Banking Sector

There is still far too much uncertainty to determine the exact implications that the Brexit vote will have on the UK banking sector. Some investors believe that the Bank of England will take immediate steps to counter the recent devaluation faced by the GBP. On June 30th, Mark Carney announced his intention to cut interest rates to ‘tackle the economic fallout from Brexit’ (The Guardian). This statement sent chills down the spines of UK banks, as lower interest rates effectively shrink their profit margins through the loan-savings differential. This step further adds to the hostility within the UK banking climate, and will also affect everyday citizens through lower earnings on their savings. On top of that, a slowdown in the UK economy is being predicted. Goldman Sachs recently cut its forecasts for growth to 0.2%. There are also expectations that the UK housing market will slow, and unemployment will rise, pushing up bad debts – all of which makes for an uncomfortable environment for UK banks.

All of the aforementioned risks are amplified by the general uncertainty regarding the future terms of interaction the UK will have with the EU in the fields of trade and finance. Many of the regulations that govern the interaction between UK banks and the Euro finance sector are managed at the EU level, meaning that regulatory changes will need to be negotiated and restructured over the course of the two-year negotiation period. The EU is by far the UK’s biggest trading partner, with EU nations purchasing 44% UK imports. If the UK loses full access to the EU’s Single Market, exporting to Europe will become increasingly costly. Even a well-negotiated limited-access deal with the EU would provide the UK with far less access to the Single Market than it had it before. The UK financial and business services sector would be especially hurt, which is unfortunate as they represent a significant positive contribution towards the country’s balance of payments, and constitute more than 5% of GDP.

The Negotiations Determine Everything

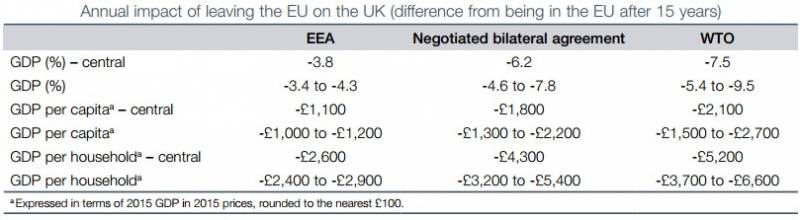

The UK Government has estimated that the restructuring of old EU trade deals and agreements will result in 10 or more years of uncertainty, as renegotiations take place between the UK, the EU, and many other involved nations abroad. It has been generally accepted that there are three possible trade models which could be utilized by the UK, now that it has left the EU. The selection of this new trade model greatly affects the UK banking sector, and the investment climate in general.

Membership within the EEA

Similar to Norway, the UK could remain within the European Economic Area (EEA) to allow for continued free-trade, while leaving the EU. The EEA comprises the 28 member states of the EU, along with Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. It extends elements of the Single Market to these members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). To join the EEA, the UK would first need to obtain EFTA membership, requiring the unanimous agreement of EFTA members. The UK could then join the EEA with the unanimous agreement of all EEA countries. As a member of the EEA, in terms of access, the UK:

- Would have tariff and quota-free trade with the EU on most goods, with the exception of agriculture and fisheries

- Would be outside the customs union, meaning that UK firms exporting to the EU would face additional administrative costs

- Would have access to the level playing field, through reduced non-tariff and other barriers to trade

- Would not be party to the EU’s trade deals with the rest of the world

It is very unlikely that the EU will be agreeable to such a deal, where the UK is allowed to take advantage of the economic benefits of a trade union while removing itself from the obligations of free movement, and obeying laws from Brussels. Italian Prime Minister Renzi openly stated that the UK should not be allowed to ‘pick and choose’ which benefits it receives, and which obligations that it’s exempt from within its dealings with the EU. Similar sentiment was echoed from Germany, when Angela Merkel called for the UK to invoke Article 50 immediately and begin the process to leave the EU.

Negotiated Bilateral Agreement

Another potential alternative is that the UK establishes bilateral trade agreements with the EU, without joining any formal trade group. Switzerland has a complex set of over 120 bilateral agreements, which represents the most developed bilateral relationship with the EU. Turkey is in customs union with the EU, and has a long-term aspiration to become an EU member state.

Negotiating a brand new UK-EU bilateral agreement would be a complex and tedious process. Approval from within the EU itself could take an extended period of time, as negotiating that agreement could also require unanimous agreement by the remaining 27 member states and ratification by their national parliaments. The European Parliament would also need to give its approval. Reaching agreements on such a wide range of issues, with a large number of negotiating partners, each of which would seek to defend their individual interests, is likely to be difficult.

Canada’s agreement has taken 7 years and is not yet in force, while Switzerland’s set of agreements have been negotiated over 2 decades.

WTO Membership

The third and final option available to the UK is that it does not attempt to establish any form of preferential trade with the EU, and relies on its WTO membership for trade. The WTO provides a global framework for trade relations between 162 countries. As stated above, in the absence of any other arrangements between the UK and the remaining EU countries, the UK would fall back on its WTO membership as the basis of its trading relationship with the EU in the same way as, for example, Brazil or Russia.

Falling back on the WTO would be the least integrative form of trade that the UK could have with the EU. It would be a definitive break, offering none of the economically important features of the EU. Under the WTO alternative the UK would be:

- Subject to the EU’s common external tariff on imports

- Outside the customs union

- No longer an automatic beneficiary of future efforts to create a level playing field for trade through reduced non-tariff and other barriers to trade

- Excluded from the EU’s trade deals with the rest of the world

HM Treasury has released an assessment of the economic losses lead by the Brexit:

Source: HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives

Investor Sentiment Going Forward

Across the globe, analysts and equity researchers are cutting EPS estimates, intimidated by the low GDP growth prospects and loose monetary policy coming from the Bank of England. Fitch and S&P have lowered the UK’s credit rating to AA, and Moody’s has also lowered their rating. Market volatility has been further amplified by the geo-political uncertainty surrounding Scotland, North Ireland and Gibraltar, as these nations now have the momentum required to seek independence from the UK. With all of these factors contributing to the blanket of uncertainty covering the entire United Kingdom, we do not recommend purchasing any further UK financial assets until some policy has been established; guiding the way forward for UK trade with the EU.

27/12/2016 at 11:42 am

Very efficiently written article. It will be helpful to anybody who usess it, including myself. Keep up the good work – looking forward to more posts.